The Eruption

Previous History

1847 painting of Native Indians watching Mt St Helens erupt, by Canadian Paul Kane - Royal Ontario Museum

Throughout history, Mt St Helens has been 'active' during four distinct periods. These have been 40-35, 20-18 and 13-8 thousand years ago, in addition to the modern period (the last 4500 years). As part of the pacific 'ring of fire', it is renowned for explosive eruptions.

In the 'modern period', there have been a series of very large eruptions. One that was significant occurred around 1900 BC and is estimated to have emitted over three times as much material as the 1980 eruption. From around 1200 BC to 800 BC, there were high frequencies of smaller scale eruptions. At roughly 400 BC, the cone that was responsible for the 1980 eruption was created, and that coincided with a change in the composition of the magma; the addition of basalt. Another large eruption occurred in the first century BC, filling nearby valleys with lava, preceding a short period of dormancy.

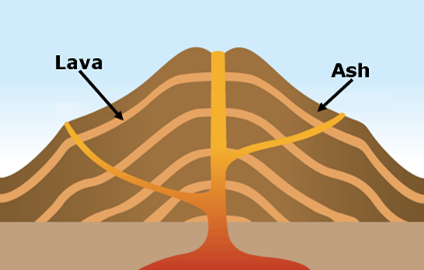

In the fifteenth century AD, two eruptions stuck on a scale equal or greater to that of the 1980 eruption, in 1480 and 1482. Over the next hundred and fifty years, variations in the silicon content of the magma created distinct layers in the mountain, which grew to its greatest ever height as the result of several gentle eruptions, emitting lots of lava.

The next period of volcanic activity started in 1800 and lasted approximately 60 years. The 1800 eruption was very similar to the 1980 one in terms of amount of material released and the size of the ash cloud; differing in explosivity (the 1980 eruption destroyed a large segment of the mountain, especially the north face – coincidentally the position of the vent during the 1800 eruption). A dozen or so smaller-scale eruptions occurred over the next sixty years; the last volcanic activity before 1980.

The Build Up

Mt St Helens before the 1980 Eruption - USGS

After being dormant for over a century, Mt St Helens finally started to show signs of awakening in 1980. Minor earthquakes were measured, occurring as early as March 15, leading seismologists to believe that after 123 years, there was now magma movement again within the magma chamber of the volcano. These earthquakes continued over the following weeks, throughout April and May, peaking at the point where earthquakes of over 4 on the Richter Scale were on average occurring eight times per day.

On March 28, a massive jet of steam blew a crater in the ice cap at the summit of the mountain. The crater had reached a diameter of 400m by the end of the week and was joined by two massive lines of cracks in the ice. Perhaps the most worrying incident to scientists was the 150m bulge in the northern face of the mountain, caused by the rising pressure of the magma.

By May 17, over 10 000 earthquakes had been recorded, and scientists had also noticed minor avalanches at the peak of the mountain, caused by the earthquake activity.

The Eruption

Mt St Helens a few days after the 1980 Eruption - USGS

At around 8:32 in the morning, a massive landslide slid the bulge and summit away down the mountainside, caused by an earthquake of 5.1 on the Richter Scale twenty seconds earlier. The landslide broke world records as the largest in recorded history, in the process removing a lot of the rock covering the magma chamber, making what was left very unstable. The pressure that had built up was suddenly released, resulting in an explosion which ripped apart the summit and the north face (where the landslide had occurred) of the mountain. The lateral explosion created a massive column of gas and ash that rose fifteen miles into the sky in as many minutes.

A secondary eruption through the recently created crater occurred about an hour later, pouring magma and pyroclastic flows down the mountainside. As the eruption melted the ice cap on the volcano, water was added to the lava and debris to create lahars. The largest lahar was formed from the deposit of material at the bottom of the mountain caused by the landslide, when it mixed with water and lava pouring down the mountain, as well as water from the nearby Spirit Lake, which had flooded. It entered a nearby river, before joining the larger River Cowlitz, leaving a trail of destroyed houses and bridges behind it. The eruption continued for several hours, pouring material into the air and nearby valleys. In all, over 520 million tons of ash were released into the atmosphere.